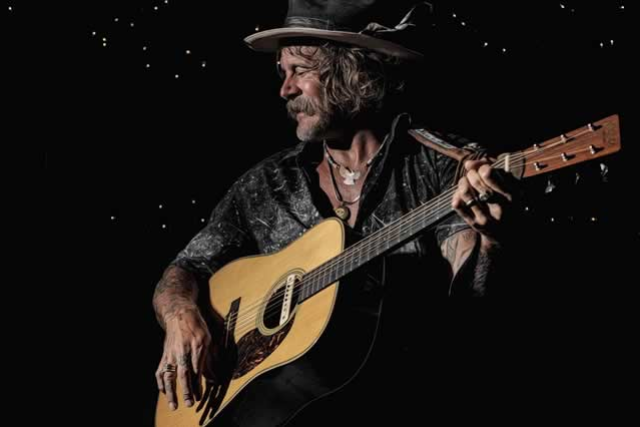

Donavon Frankenreiter

Donavon Frankenreiter, "The Heart"

Donavon Frankenreiter's new album, "The Heart," officially marks the start of the singer-songwriter's second decade as a solo recording artist. It's been over ten years since the release of his self-titled debut, and in that time he has grown, not only as a musician, but also as a man. He's raising a family and nurturing two creative careers-one onstage, one in the waves-but on top of all that, he's still learning what makes him tick. And so, naturally, he named his album after his ticker.

"All these songs are as close to me singing from the heart as I can," says Frankenreiter. "It's a complete record; the songs are intertwined. I had to call it 'The Heart,' that was the theme of the record."

The songs here are seriously sentimental, without question the heaviest material he has released to date. Part of that inspiration came from his co-writer, the prolific songwriter Grant-Lee Phillips, with whom Frankenreiter had collaborated in the past on his album "Pass It Around." He recognized the ease with which the two worked together and sent Phillips a handful of new tunes and ideas. He was astonished at the brilliance of the songs that came back, and so quickly, but also by one of Phillips' suggestions in particular.

"Grant told me, 'You should make the most intimate and honest record you've ever made,'" says Frankenreiter. "So these songs are simple and intimate and honest, they aren't cheeky. There's some ups and downs-I love writing positive songs and happy tunes, but there are some downers here. I feel like it's where I'm at, 42 years old. Every one of these songs means a lot to me. They're from the heart."

To record them, Frankenreiter booked two weeks of studio time in May of 2015 at Blue Rock Studios in Wimberley, Texas. But unlike the privacy afforded by most studios, these sessions were to be live-streamed on the Internet in a soul-baring exhibition for his fans-talk about intimate and honest. With just two bandmates and a studio engineer, Frankenreiter knocked out a song each day and recorded the entire album in full view of a watching public. He had never been so inspired, and embraced every aspect of the situation: the landscape, the lodging, the isolation, the overall challenge.

"We went in saying, 'Let's make the best record we can that we enjoy,'" he says. "And not that I didn't feel that way about my other albums, but this was the one that felt the most natural. Even the way we made it, too, a song a day. I went into it feeling a little pressure, this whole live-streaming thing; if we hit a rut the first day, we're screwed. But the first day we cut 'Big Wave,' and it was off to the races."

The nature of the recording environment removed any "fuck-around" time and replaced it with the utmost efficiency and excitement. As Frankenreiter says, it was an experiment, and it invigorated the band, resulting in their most cohesive process to date.

"There's something magical about Blue Rock Studios and Wimberley, Texas," he says. "It's really powerful, that's one spot that is really bitching. This place is beautiful, a huge estate on 50 acres, cows walking by the windows while you're recording-this open, amazing wilderness. We lived in the studio, and to record there and never have to leave, that's the first time I ever made a record that way. Every morning you wake up and hit it again. I was in such a bubble; it was all about the music. I think about it now and it's emotional."

Throughout the process, he continued to have more encounters of the heart-some more literal than others. While recording "Woman," it was noticed that a Tibetan singing bowl found in the studio was in the same key as the Heart Chakra, one of the centers of spiritual energy in the body, and both just so happened to be in the same key as the song. Someone played it, and the sound made the final cut on the album.

Elsewhere, the song "Little Shack" was culled from someone who shares Frankenreiter's heartbeat: his 12-year-old son, Hendrix. "One night, at home in Hawaii, I was trying to write songs and my son was jamming on his electric," he says. "I was like, 'What is that song?' and he said, 'It's just something I've been working on.' He taught it to me, and I recorded it that night and sent it to Grant. Twenty-four hours later, Grant sent back the words. It kinda has that vibe of two people getting together: it doesn't matter where you are in the world, I got everything I need right in front of me. It sounded like I wrote it, and Hendrix wrote the music. That was the first time that's ever happened."

Other moments on the album, like "Sleeping Good Night," "The Way You Catch the Light," "When the River Bends" (co-written by Graham Colton and Phillips), and the aforementioned "Big Wave," highlight emotions but also have about them an ease, a familiarity, a confidence that only comes from experience. These are songs that Frankenreiter could not have pulled off in his first decade. There is a rollicking comfort to them, but also those serious sentiments of love and loss, faith and joy and, more than anything, self-examination and freedom.

"I feel really lucky that I got into the game when I did," he says. "I'm still lucky I'm able to make records and that we have a fan base and are able to tour. I started my own record label; it's a way for me to make my own music the way I want to, on my own time, and to put it out my way. So many things have changed and I feel a little wiser than ten years ago. I learned a lot over the last decade, it went by really quick. It's fun to have a new album done and to hit the road with a bunch of new songs, it rejuvenates you to do your thing."

And, for now, Frankenreiter's "thing" may be compassion. Perhaps most heavy on "The Heart" is its final song, "California Lights," a tune written about Frankenreiter's father's battle with Leukemia. "It was written about my dad, who was dying during the making of this record. He died about two weeks after we finished it. It was pretty intense, a heavy song to record. I did that song in its completion three times, that's

all I could only make it through. The live take of me playing the guitar and singing was the only way I could do it. I was seeing the heart everywhere."

In those moments of emotional heaviness, Frankenreiter reaches for his guitar to guide him, for an escape. "I felt like I was completely in a bubble the whole time I recorded, I was so inside the music. I cried when I left the studio, and the guys in the band did, too; it was radical. It was like going back to reality. That's what music does, you can definitely escape."

A decade into his career, Donavon Frankenreiter has learned to listen to his ticker above all else. Doing so has allowed the light to come in from all the corners of his world, even those where there is darkness. Sharing the load with those he trusts, and especially with those he loves, he has seized the opportunity to take control of his craft, on his own terms, and to follow his own beat.

"I went into this album saying I wanted to make songs I love," he says. "Whatever feels right, go ahead and record it, and worry about what happens after, afterwards. I'm proud of it. I go back to the title of the album, and in the song 'You and Me,' that chorus: 'It's gotta be from the heart/for it to start'... There's so many things going on out there, everybody's moving to the beat of a different drum, but I feel like all good things start from the heart."